Table of Contents

This paper is about comparing two personal knowledge management systems from different points of view: CODE and notebox. A brief introduction of both:

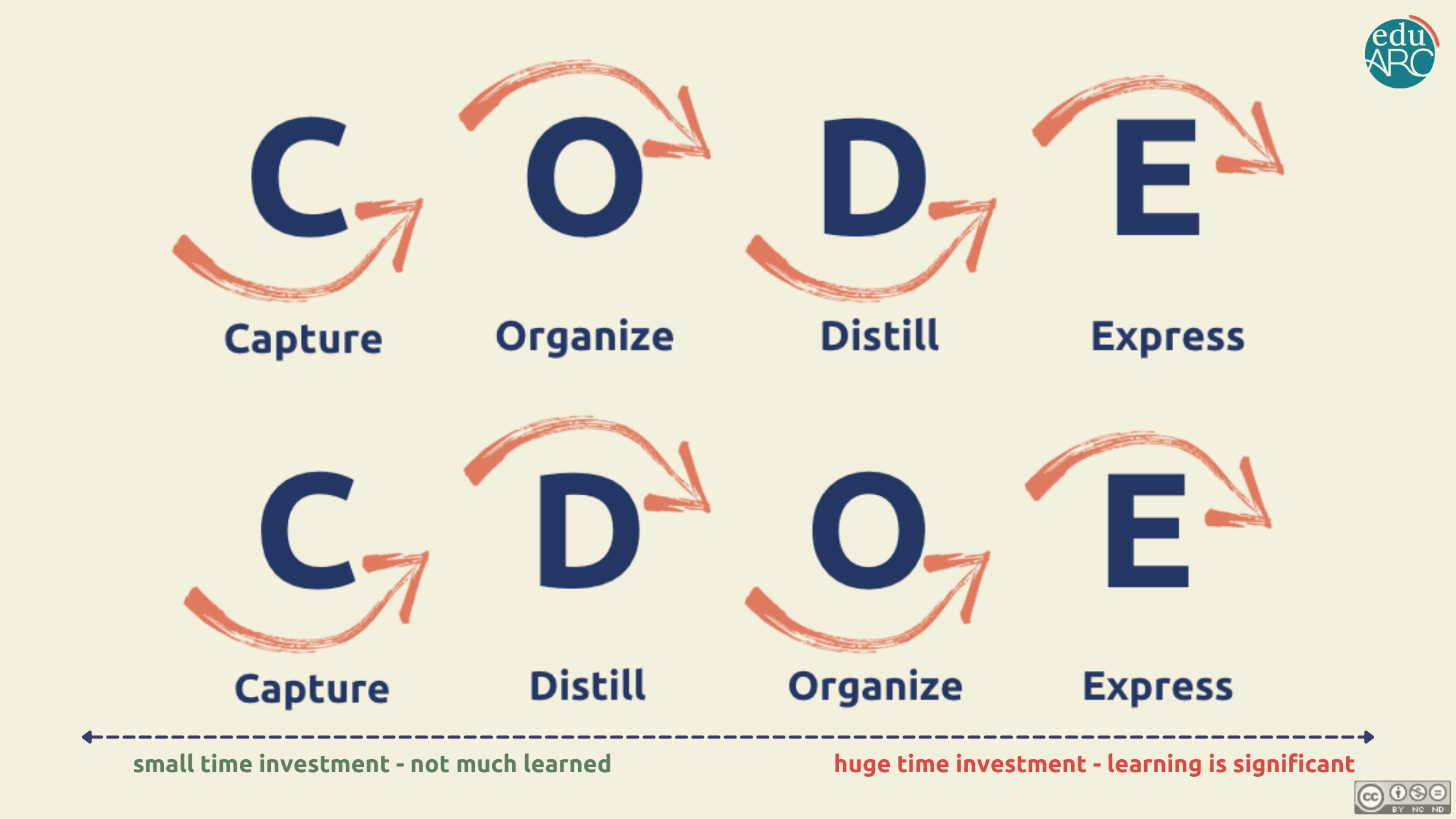

- CODE stands for the system developed by Tiago Forte, and which he teaches in his course and in his book Building a Second Brain: CODE: Collect, Organize, Distill, Express. These four states help us visualize the path a piece of information takes from the moment we capture it to the moment we do something with it. It is a flexible and, in our opinion, useful simplification of the creative process.

- The slip box method has its origins in the analog version of German sociologist Niklas Luhmann, who managed 90,000 slips of paper in a slip box (for a glimpse of his slip box, see here). Each note contained an idea and with the help of his note box he wrote 70 books and more than 400 articles (in the Niklas Luhmann Archive you can see the digitization project of his system). Today there are digital tools (note apps) that can be used instead of the analog system for taking notes.

In this paper, we will use CODE as a basis to compare the two systems. What is clear is that the purpose of the systems is the same:

- To manage ideas for use in projects.

- Serve as a tool to externalize thinking.

- The focus of both systems is not on organization, but on interaction and creation.

Let's start with CODE

The core philosophy of CODE is based on working with information in a project-oriented way. Let's look at this with an example, but not without emphasizing that this is a flexible process that doesn't have to be followed step by step.

Collect

In a newsletter we love, they reference an article about writing stories as a means of exploring one's childhood. We don't have time to read it right now, but it sounds super interesting. We capture it in our read later app or inbox.

When we have a moment or feel like it, we read it. We underline after the first level of running summary, trying not to underline what we already know, but what surprises us or what we disagree with. If necessary, we write a few notes about what something mentioned in the article means to us.

Organize

After we read it and underline it, we get into the project mentality. Now it's time to organize that note with your own underlining and annotations (but not all the text, even if there is a link). We need to decide where to keep it, and we will do so according to the feasibility of the note and within the PARA framework (projects, areas, resources, archive). Do we have a project where story writing or the writing angle is relevant to exploring childhood? That would be ideal for this note to "activate" for a project as soon as possible. If not, we ask the same question, changing projects by area and resource. It is very likely that we will find something that fits. For example, I would put it in my "writing" area.

The idea is not to do much with these notes from now on unless we find a use for them, a project that it fits into. Two examples of how I would proceed from here with synthesizing and expressions (our own examples):

- I want to write a post for this blog about writing as a means of exploration (of us). It is clear that I will find this note, either through search or because it is in my "writing" section. I'll move the notes I want to use to the blog post project.

- Let's say it's my mom's birthday in a few months and I'm thinking about gifts. I create a project called "Gift Mom" in my notes app. I start going through my notes by keyword search and looking through my resources and areas. My mom likes crafts, plants, cooking and is a family person. I find several notes on these topics and move them into the project.

Distill

From here we start synthesizing according to the next steps of the running summary, so mark in bold/yellow what we are interested in from these notes for this particular project, since we probably haven't marked anything in the note yet.

If we've already used them for other projects and we have underlined passages, see if we can use them as is or if we want to take ideas in our own words and adapt them to the current project or change the underlining. Flexibility in the process is the most important thing.

We read and filter which of the notes we pulled into this project are relevant and which will serve as sources for our project.

Express

Now it's time to put the pieces we have together, put our stamp on them, and enrich what we've captured, organized, and distilled with our perspective. In the case of the blog post, it's very clear: it's about writing from the sources and notes we have, or using them as examples. In the case of the gift for my mother, it occurs to me that the note I gave as an example at the beginning could help me write a story with my brother about our childhood and give it to her to read to her grandchildren one day.

When we follow CODE principles, we treat notes "just-in-time" in the sense that we "get on" with them only when we need them. We read and underline what we have captured and organized not for the sake of it, but just in case we want to use it in a particular project. We are opportunistic with information and only put effort into it when we know we will use it for something specific. We capture now, yes, but we organize, distill and express it later and with concrete projects in mind.

The Zettelkasten method under the magnifying glass of CODE

However, if we follow the slip box system, the principles change. We abandon the just-in-time philosophy and the idea of emergency comes into focus. In our opinion, the most important difference between these two information flow systems is that the order of steps in the information flow is changed: CODE (SOSA) becomes CDOE (SSOA), Collect, Synthesize, Organize, and Express. I take the same example as before:

Collecting in the "Zettelkasten"

In a newsletter we love, they link to an article about writing stories as a way to explore your childhood. We don't have time to read it right now, but it sounds super interesting. We capture it in our read later app or inbox.

When we have a moment or feel like it, we read it. We underline and try not to underline what we already know, but what surprises us or what we disagree with. It is important that we write down succinctly in our own words what interests us about the ideas in the article and refer to the page(s) or source. This is one of the differences with CODE. We already write a brief note about what we read, why it is relevant, or what the author:in says, but in our own words. These are the bibliographic notes of the notebook.

Before we continue, it is important to mention that sometimes it is useful not to underline or take notes right at the beginning of the reading. If we are not very familiar with the topic we are reading, it does not make much sense to start underlining because many ideas can catch our attention and seem new and interesting.

Synthesize or elaborate in the "Zettelkasten"

Once we have these bibliographic notes with the ideas we want to come back to in the text, it's time to distill, synthesize, or as I would call it if the notebox had its own acronym: elaborate. In this step, which comes before the organizing step, we write permanent notes. These notes are distinguished by the fact that they contain only one self-explanatory thought, are written in our own words, and expand a little on the thought we wrote down in the bibliographic note. In the permanent note, we don't summarize the information we've read, but we put it into our context, giving a response, as it were, to what we've just read.

This is why Luhmann said that the notebook was his interlocutor. The notes he wrote were already finished building blocks that he could use in his texts, because he wrote them with his own conclusions and thoughts.

So when we create a permanent note on an idea from an article we have read, we need to consider already in this second step why it is relevant to our work, our interests, and our context.

Organize in the "Zettelkasten"

In the Zettelkasten, there are no folders or categories where we can store our notes. You work with indexes and content maps. After creating a permanent note (whose format is standardized, as we saw in the previous step), we need to try to find a train of thought where the note fits, and link it to either the index or a content map.

The concept of an index or content map is similar to PARA areas, topics that we maintain over time and into which we bring writing as a tool for whatever, for example, as in our example. But they could also correspond to a specific project, something we're writing, like the entry I talked about in the example.

It's curious that the example I gave earlier of the gift for my mother doesn't seem to have a place in the Zettelkasten and does in CODE. This is an indication that CODE can cover all facets of your life.

Although the Zettelkasten is also for ideas that can be turned into projects, managing less mundane and less intellectual projects seems much less relevant. Our theory is that encouraging the emergence of ideas means that urgent or more "practical" projects have no place in the Zettelkasten. I'm interested in your thoughts on this.

Express in "Zettelkasten"

As I mentioned at the beginning: The goal of both systems is that we can express our ideas and create something from all the information we have consumed. I've already mentioned the emergence of ideas as the cornerstone of the Zettelkasten method, the idea that topics are developed from the bottom up, so we don't define them from the beginning.

Although it sounds ideal, we can't always work this way because sometimes we have deadlines and a more urgent or just-in-time way of working is required, where topics are chosen beforehand, possibly not even by oneself. That's also a good thing.

Conclusions

The oxygen of the CODE system are the projects: They are what allow us to get feedback on whether something is working or not, it is the moment when we elaborate in our own words what we have read/consumed before. However, the oxygen of the Zettelkasten method is the permanent notes. They come much earlier than in CODE, but they are also much more time-consuming and intensive to create; you can think of them as mini-projects.

When is the CODE workflow useful and when is the Zettelkasten workflow useful? I think it's very interesting to give us space to interact with the information in one way or another. There are times when it's worth working on developing ideas from the top down, with specific projects and deadlines and without too much of an influx of ideas. It's like sending experiments into space to see if the ideas survive or not.

There are ideas and topics that deserve the emergency treatment that the Zettelkasten gives us, ideas that ask us to cook them, that need more space, time and dedication. For one reason or another.